This story appears in SLAM 251. Shop here.

South Sudan, the youngest country in the world, is, as I write this, the proud home of a national basketball team hooping in the Paris Olympics, an outrageous accomplishment for a strife-ridden nation that has only existed since 2011.

Even if this program was led by people that no one at SLAM had ever heard of, the accomplishment is so grand it warrants our attention. Alas, it’s led by two of our favorite people in the sport, gentlemen who have been bringing smiles to us and all who love the game for almost as long as SLAM has been around: Luol Deng and Royal Ivey.

Deng, who most of you should know from his longtime NBA career, if not the many remarkable steps in his life path before or since, is the crux of this story. I learned about Luol around 2000, when his older brother, Ajou, was a highly touted recruit at UConn and agents started whispering about a younger brother they called “Louie” who would be even better than Ajou. By late 2002, I was hanging out at Blair Academy for a feature on then-Blair senior Luol and his teammate, Queens’ legend and future NBAer Charlie Villanueva. Luol was certainly one of the most impressive teenagers I’ve ever spoken to (as if writing about high schoolers for SLAM wasn’t enough exposure, now I have a teen of my own), and he came with a breathtaking backstory.

Born in the southern part of Sudan when it was still one country in the throes of a civil war, Luol and his mother and siblings fled the country for a safer life in Egypt in 1990, and in ’94, they reunited with his politician father, Aldo, in London. Luol spent some formative years in the South London neighborhood of Brixton, picking up a proper love for Arsenal and football but also hooping all the time. And growing. Luol followed Ajou’s footsteps in coming to America for prep school, which is how we found him at Blair. And he wasn’t just a nice kid playing some ball while getting a quality education to set himself up for a college scholarship; he was the second-best player in his high school class. Literally, pretty much every 2003 high school ranking system or all-star game had a No. 1 and No. 2 player. Luol was No. 2. No. 1 was LeBron James.

Deng went to Duke for one season, leading the Blue Devils to the Final Four (where they lost by 1 point to Villanueva’s UConn team, ironically). Deng was the seventh pick in the ’04 Draft and began a 10-year stint with the Bulls that featured two All-Star appearances, two seasons leading the NBA in minutes per game and a ton of playoff games. This was mostly the Thibs-Derrick Rose Bulls, and Deng was the engine that made them go. He played five more seasons after Chicago to give himself a tidy 15-year career in which he was absolutely beloved by his coaches and teammates and always a pleasure to chat with in locker rooms (especially if I led with Arsenal check-ins).

Deng was not satisfied just being a star on the court, though. Off it, he created the Luol Deng Foundation and was regularly going back to London and Africa to take part in various charitable efforts and basketball events designed to grow the game. In 2021, he was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire, which is one of those very British things that, at least in Great Britain, means that he should be presented as Luol Deng OBE; becoming “Sir Luol Deng” might happen in the future. At the same time that he was making his mark with charitable work in his adopted home of England, Deng was reigniting his relationship with his real home of South Sudan. He’d been named President of the South Sudan Basketball Federation in 2019 and began spending more time there. “Imagine your family fleeing a country and going to find life somewhere else,” Deng says in a mini-doc about the team qualifying for the Olympics that was shared with SLAM. “And instead of you being in that other country and forgetting about South Sudan and enjoying your professional basketball career, you’re actually committing to come back and play for that same country that you fled because of the war, and you’re the one now bringing all this positivity to it.”

Beautifully said, Luol. Unsurprisingly for a country of less than 13 million that has been around only 13 years—and suffered through internal fighting and development challenges the whole time—building a basketball program was not a priority. But there is a heritage of the sport there and in the people who come from there, beginning with famed NBA shot blocker Manute Bol (who originally inspired Deng and his brothers) and continuing with Deng, former Syracuse star Kueth Duany, Manute’s son (and SLAM fave) Bol Bol and heading into the future with young stars like Khaman Maluach, a 17-year-old incoming freshman at Duke who is projected to be a top-five pick in the 2025 NBA Draft.

Since his appointment as president of the SSBF, Deng has instilled structure around the team and sought to get the best players from the South Sudanese diaspora suiting up for the country of their roots. Things coalesced last summer when South Sudan, playing in its first-ever FIBA World Cup, earned an Olympic berth by finishing as the highest-ranked team from Africa.

If Deng has been the SSBF’s Jerry West—the retired legend now building a roster with guile and conviction—Royal Ivey has been their Pat Riley, a retired role player turned motivational master as head coach.

Ivey, currently an assistant coach with the Houston Rockets, has been on my radar since 1999, when he led what was once unquestionably the #SLAMfam’s favorite high school, Queens’ (NY) Cardozo (shout out Ronnie Z and Coach Naclerio!), to an NYC PSAL title, earning MVP honors in a 57-47 win at Madison Square Garden that gave Naclerio, now the winningest coach in New York State public school history, his very first title.

After graduating from Cardozo with that ’99 title on his CV, Ivey spent a post-grad year at Blair where he played alongside…a young Luol Deng. “Luol has been like my little brother since I met him his freshman year at Blair,” says Ivey over Zoom from Kigali, Rwanda, where the South Sudan team is holding pre-Olympic training camp. “I was older and I wanted to protect him, but he was also motivation to me. I was 17 years old and he was 13, waking me up at 6 a.m. to get in the gym. Then we were in the same draft class and we’d hang out in Chicago and stay in touch. Later on, I worked his camps in London.”

Ivey was a 6-3 2-guard who couldn’t shoot all that well, but he always played hard—especially on defense—and he was a great teammate. He played four years at the University of Texas, reaching the ’03 Final Four and making such a mark with his intangibles that he was the 37th pick in the ’04 NBA Draft despite four-year college averages of 8 points, 3 rebounds and 2 assists per game.

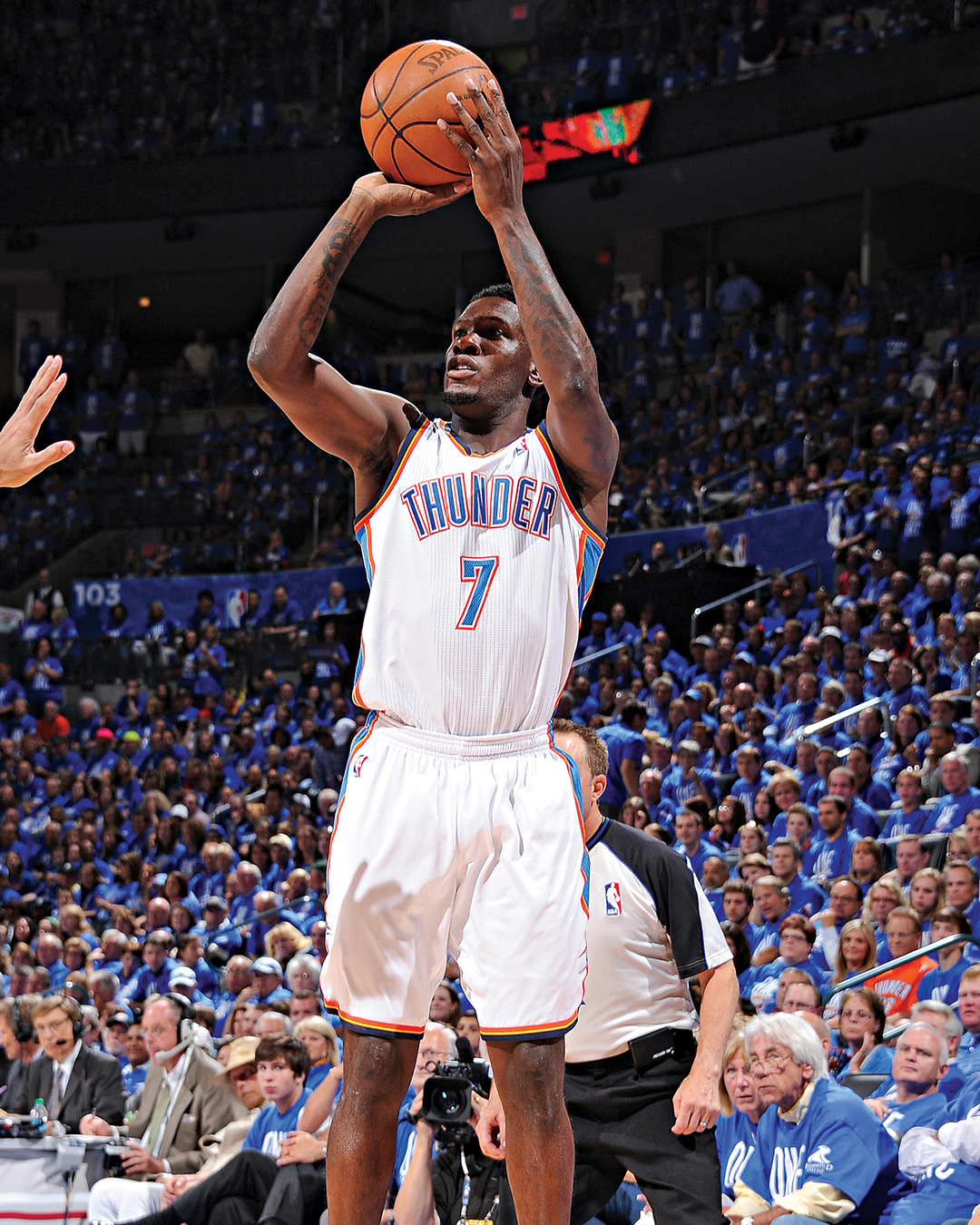

Ivey’s numbers were even lower in the pros, but he lasted a decade in the League and then, after his final stint with the Oklahoma City Thunder in 2014, OKC GM Sam Presti asked if Ivey would serve as an assistant with their G League team, the Blue. Ivey’s been on the coaching grind ever since.

“The way I got this job was crazy,” Ivey shares today. “I was watching Luol coach [South Sudan] on Instagram. I’m coaching in New York. [Then-Knicks head coach David] Fizdale gets fired. I was looking for a new opportunity and I was intrigued about helping Luol move forward. I told him I’d love to be part of the staff. You don’t have to be a part, Luol told me. I want you to run this thing.”

And with that, the two—friends through two wild decades in the business of basketball—were off and running, coming out of the pandemic with a fast playing style and the buy-in of more and more good players. South Sudan has plenty of work to do as a nation, but when the basketball team, nicknamed the Bright Stars, plays and wins, there’s a national pride that is not typically on display. “We’re here to put South Sudan on the map,” Ivey says. “We’re here to heal. To bring a country together through sports is something life-changing. I’ve been there and touched the ground and touched the people.”

Adds Deng in the mini-doc: “I want these guys to realize what sports does for the country. Sports is gonna be the vehicle of unity.”

Clearly, there’s a full-length movie to be made here. I know I’ll watch it.

Photos via Getty Images.