On this day, ten years ago, the Formula 1 paddock received a harsh and brutal reality check. A stark reminder of the ever-present dangers inherent with racing the quickest cars on the planet.

The two decades that followed the unforgettably ugly events at Imola in 1994 were the safest the sport had ever seen, a direct result of sweeping changes driven by a shared commitment from teams, drivers and the governing body to never experience another grand prix weekend like it again.

As a result of these efforts, an entire generation of fans grew up with the luxury of never knowing how it felt to watch one of their heroes die behind the wheel of a Formula 1 car. Yes, there had been injuries. There had also been deaths – marshals Paolo Ghislimberti and Graham Beveridge had lost their lives volunteering for the sport they loved. But drivers were different. No matter how horrific or violent the crashes, they would either be rushed to hospital and stabilised – such as Mika Hakkinen in Adelaide 1995 – or simply climb out of their wrecked cars under their own power.

In that time, only two people could have been considered as dying from Formula 1-related accidents as drivers. In 2000, driver John Dawson-Damer was killed driving a 1969 Lotus 63 at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, also resulting in the death of marshal Andrew Carpenter. Then, in 2013, Marussia test driver Maria de Villota, who suffered life-threatening head injuries from a testing crash the previous year, died from suspected complications from that accident.

But October 5th 2014 was the last day that 25-year-old Marussia driver Jules Bianchi was able to do what he loved – what millions of fans admired him for. Nine months later, Bianchi’s life would come to its end, a direct consequence of what happened that day at Suzuka.

Before the accident

Twenty years prior, a wet race at Suzuka had seen a near-tragedy at the fast, uphill left-hander of Dunlop. Footwork driver Gianni Morbidelli lost control of his car in the full-wet conditions, crashing into the outside tyre barriers. The incident was covered under local yellow flags, with multiple marshals and two course vehicles entering the track surface.

Moments later, Martin Brundle aquaplaned off the circuit at the same spot as Morbidelli, sliding into the barrier and knocking over one of the marshals recovering the crashed Footwork. The marshal suffered a broken leg in the incident, which resulted in the race being stopped. Brundle was later reprimanded by the event’s stewards for “not controlling his car’s speed” in the conditions, although the driver insisted that he “was not pushing particularly hard” around the wet track due to the volume of water on the circuit.

Despite the accident, the culture around the use of localised yellow flags remained largely the same over the coming decades. The ‘best drivers in the world’ were largely trusted by the FIA and F1’s race director Charlie Whiting to obey yellow flags in the event of accidents, with many single-car accidents covered by local yellow flags by trackside marshals on track, rather than races being neutralised by a Safety Car first.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Recovering cars also meant sending recovery vehicles into the gravel trap, or even the track itself, to remove wreckage. But, again, this was often covered with local yellow flags. There was no such concept, in Formula 1 at least, of a ‘Virtual Safety Car’ or ‘Full Course Yellow’ – which would be introduced into the FIA’s World Endurance Championship at the start of 2014 – compelling drivers to slow down to a track-wide speed limit.

However, not everyone was comfortable with recovery vehicles being used in this way. After Tyrrell driver Tora Takagi crashed heavily at Hockenheim’s first corner during qualifying for the 1998 German Grand Prix, Brundle, now an ITV commentator, did not hide his discomfort seeing a tractor in the gravel trap as cars continued to drive around the circuit, albeit under double-waved yellows.

“This always terrifies me when you get a John Deere coming into play,” Brundle muttered to co-commentator Murray Walker. “If one car can make it into there, all of the cars can make it that far.

“One day, somebody’s going to end up underneath that tractor – it really terrifies me.”

The Bianchi tragedy

On lap 42 of the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix at a soaking wet Suzuka circuit, Sauber driver Adrian Sutil lost control of his car rounding the uphill Dunlop curve, spinning into the tyre barriers. The incident was covered under local double yellow flags. Marshals immediately entered the track, with a recovery vehicle driving out to also attend to the scene.

“Sutil’s seventh retirement… but where is the car? How quickly can they get it out of the way?,” Brundle mused on the Sky F1 broadcast. “Are others going to be aquaplaning or spinning off at the same point? Something that’s a bit sensitive to me, because it happened to me…”

Literally seconds after speaking these words, Bianchi lost control of his Marussia entering Dunlop in near identical fashion to Sutil one lap before him, and Brundle 20 years prior. Bianchi hit the crane parked next to the Sauber. His helmet struck the underside of the machine at a recorded speed of 126kph, the immense force of the impact resulting in immediate and severe head trauma – not even the state-of-the-art protection offered by his helmet proving enough to ensure his safety.

Bianchi was extracted from his car and driven by ambulance to the Mie General Medical Center in Yokkaichi – the medical helicopter that otherwise would have flown him to the hospital having been unable to take off in the poor conditions. Two days later, Marussia announced Bianchi had suffered a “diffuse axonal injury” to his brain and was in a critical but stable condition.

Several weeks later, Bianchi was transferred to Le Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice in his native France for further treatment. He never regained consciousness. In July 2015, the Bianchi family announced that Jules had died from his injuries. He was 25 years old.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

After the tragedy

The horrific accident left Formula 1 and the FIA reeling. Two months to the day after the accident, the FIA published a report by their accident panel into the events of Suzuka, outlining key facts, observations and recommendations from what had occurred. The panel consisted of FIA Safety Commission president Peter Wright and several major figures in motorsport, including Ross Brawn, Stefano Domenicali, WEC race director Eduardo Freitas, F1 world champion Emerson Fittipaldi and GPDA president Alex Wurz, among others.

Their finding was that there was “no apparent reason why the Safety Car should have been deployed either before or after Sutil’s accident” after examining almost 400 yellow flag incidents over the previous eight years leading to Bianchi’s crash. They determined that the Marussia driver “did not slow sufficiently” under the double yellow flags, suggesting that had Bianchi slowed in accordance with the regulations regarding yellow flags, there should have been no immediate physical danger for Bianchi, his fellow drivers or trackside marshals.

Several recommendations for the future were suggested by the panel resulting from the accident. The first was a proposed revision to the FIA’s yellow flag regulations, allowing for a maximum speed limit to be imposed on drivers in double yellow flag zones. Other suggestions included changing race schedules to avoid regular rainy seasons and ensure grand prix starts do not take place too close to sunset outside of planned night races.

At the start of the following season in 2015, the FIA introduced the Virtual Safety Car into the sport. The VSC was first deployed in that year’s sixth round in Monaco, following a crash between Max Verstappen and Romain Grosjean. The VSC has remained in use by the championship ever since.

Even in 2011, before Bianchi’s injury and subsequent death, the FIA had begun to explore means to protect drivers’ heads from impacts in open-cockpit cars. Bianchi’s death just one example of a driver injured or suffering fatal injuries as a result of direct impacts to the head while at speed – others included Felipe Massa’s injury at the Hungaroring in 2009 and the deaths of Henry Surtees and IndyCar racer Justin Wilson. Several solutions were proposed, but the FIA pursed the driver protection device known as the ‘halo’, a titanium ring that surrounds the driver’s helmet inside the cockpit that prevents medium-to-large sized debris such as wheels from impacting driver’s heads while in the car, or from hitting structures or other cars during accidents.

The first tests of the halo on F1 cars were conducted throughout the 2016 season, with the FIA making the halo mandatory for the world championship from 2018. The device was also installed on that year’s inaugural F2 car and F3 cars the following season, before being extended to F4 cars from 2021.

Importantly, the FIA’s safety director of the time, Laurent Mekies, stressed that analysis showed that the halo would not have saved Bianchi from grave injury had one been installed on his Marussia that day in Suzuka. After analysing several historic serious and fatal accidents in single-seater motorsport, which showed the halo would have improved safety outcomes in many ‘car-to-environment’ accidents, the outcome of Bianchi’s crash would not have been affected by the halo as the impact forces involved far exceeding the capabilities of the device.

Although its design received criticism from some drivers and fans after its introduction, the halo has become a ubiquitous and accepted aspect of modern single-seater motorsport. The device has been credited with preventing several driver injuries and even saving lives since its introduction. Roman Grosjean credited his survival from his horrific fiery crash in Bahrain 2020 to the halo deflecting the barrier away from his head, while Lewis Hamilton says the halo prevented him suffering injury when Verstappen’s Red Bull climbed over the top of his Mercedes after the pair clashed in Monza in 2021.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Suzuka back under the spotlight

When the new generation ground effect F1 cars were introduced in 2022, they were deemed to be the safest ever with more driver protection reinforcements than ever before. That appeared to be proven when Alfa Romeo driver Zhou Guanyu was unhurt in his frightening opening lap crash at the British Grand Prix, where the halo was again credited with helping Zhou survive major injury while upside down, despite his rollover hoop having broken on impact.

But when the sport returned to Suzuka in September for the first time since the pandemic, drivers were confronted by haunting memories of the events of eight years prior.

Like in 2014, the race had begun in heavily wet conditions with extremely low visibility resulting from the spray kicked up by the pack of cars. After the Safety Car was deployed following a crash for Carlos Sainz Jnr at the long right hand turn 12, AlphaTauri driver Pierre Gasly arrived at the scene of the accident at pace, attempting to catch the queue ahead after pitting on the opening lap after he collected an advertising board knocked onto the track by Sainz’s crash.

As Gasly approached the turn at 200kph, he found a tractor on track off the racing line recovering Sainz’s Ferrari. Gasly immediately expressed outrage to his team that there had been a recovery vehicle on track that he had passed at speed in the wet conditions without prior warning aside from the local yellow flag – drawing parallels with Bianchi’s accident. Gasly was later handed a 20-second time penalty for speeding under a red flag along the back straight following the incident, where he reached 250kph.

After Suzuka, the FIA – now under the leadership of new president Mohammed Ben Sulayem – issued a review of the race and the actions of race director Eduardo Freitas, who was sharing duties that season with Niels Wittich. While Gasly was noted to have been driving too quickly into the accident scene, the review also found that he had been able to drive faster than intended under Safety Car conditions due to a quirk in the system resulting from his slow opening lap.

Again, several recommendations were suggested, several of which were implemented for the very next round in the United States. A warning message on the FIA’s live timing system noting when recovery vehicles were on track was introduced, with teams obliged under the rules to pass along the message to their drivers. The dual race director system was dropped, with Wittich becoming full time race director, while additional wet weather tyre testing opportunities were made to Pirelli, F1’s tyre supplier, coming into effect for the following seasons.

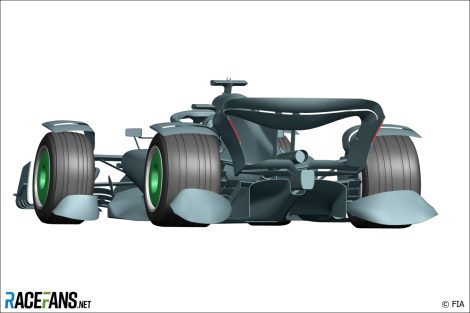

Reducing spray with the ground effect cars was also made a key aim of the FIA. The governing body conceptualised and tested multiple potential solutions to reduce spray in wet conditions and improve wet weather visibility, including spray guards behind wheels tested by Mercedes reserve driver Mick Schumacher in 2023 and wheel covers which were tested by Ferrari at their Fiorano test circuit earlier this season. After initial tests failed to produce promising results, further development work on these spray guards has now been scrapped.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Lessons still to learn

Like the pursuit of performance, F1 and the FIA’s quest to make the sport safer for its drivers, marshals and fans without stripping away the essence of what makes the series so beloved is a never-ending one. But just as it was easy to believe that there would never be a driver fatality again when Bianchi was still competing in Formula 1, no one should ever assume that is the case now.

In the years following the loss of Bianchi, tragedy struck at a grand prix weekend once more in 2019, when Formula 2 racer Anthoine Hubert died in a horrifying crash at Spa-Francorchamps that also resulted in serious injuries for fellow driver Juan Manuel Correa. Hubert’s death came despite the introduction of the halo to the series. Last year, Formula Regional racer Dilano van ‘t Hoff also lost his life from a crash in a wet race at Spa-Francorchamps – one that shared eerie parallels with both Hubert’s and Bianchi’s fatal accidents.

Largely overlooked among the natural focus on driver safety in the aftermath of the Bianchi accident was the dangers that marshals face during races, given how close track workers had come to being struck. Formula 1 has narrowly escaped further tragedy on multiple occasions over the years.

Less than a year after Bianchi’s crash, the 2016 Singapore Grand Prix saw the race restarted from a Safety Car period while a marshal was still collecting debris on the run to turn one. In 2019, Racing Point driver Sergio Perez came close to striking two marshals in Monaco who were running across the track as he exited the pit lane under a Safety Car. The following year in Imola, Perez’s team mate Lance Stroll passed by multiple marshals sweeping the circuit on the downhill run to Acque Minerale at over 250kph.

Last year, Alpine junior driver Victor Martins received a drive-through penalty in a race in Monaco for failing to slow for yellow flags as he narrowly avoided two marshals attending to an accident. Post-race procedures were permanently altered last year after an alarming incident at the end of the Azerbaijan Grand Prix, when Esteban Ocon pitted on the final lap, only to be greeted by a pack of photographers in the fast lane taking their places for the post-race parc ferme.

In the aftermath of the Bianchi crash, the FIA’s accident panel expressed that it was “fundamentally wrong to try and make an impact between a racing car and a large and heavy vehicle survivable.” Instead, they stressed it was “imperative to prevent a car ever hitting the crane and/or the marshals working near it.”

Ten years later, there are several reasons why Formula 1 is now safer than ever before – many of them a direct result of the events of October 3rd 2014. From the halo, which could have saved Jules Bianchi’s life and has likely saved many others, to increased sensitivity around accidents and how they are handled by race control, so much is already in place to help ensure no similar tragedy is ever allowed to happen again. However, the deaths of Hubert and Van ‘t Hoff show driver safety can never be taken for granted even in 2024, nor can the dangers posed to pit crews, marshals or even spectators.

But Jules Bianchi’s legacy in Formula 1 is far more than how the sport he loved has become safer in his name. Like Ayrton Senna, Roland Ratzenberger and so many of his peers before him, Bianchi will continue to be remembered and celebrated for what he achieved in F1 as well as respected for everything he surely would have gone on to achieved if he had only been granted the chance.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and

Formula 1

Browse all Formula 1 articles